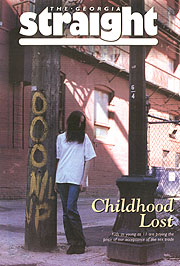

Kids as young as 11 are paying the price for our acceptance of the sex trade [cover]

p. 15.

Childhood Lost

Pimps are luring kids as young as 11 to sell themselves on Vancouver's meanest streets -- by Tara Shortt

"We're planting bean seeds," says the young girl as she and her boyfriend clear away broken bottles from a narrow trough of soil squeezed between two concrete driveways. She is clearly tickled by her soil-tilling adventure, and she offers to show me around the yard of her house. "These are my tulips," she says, pointing to a half-dozen tufts of budless leaves, "but someone stole all the flowers.

"We planted beans here too," she says, pointing out nearby parallel rows in the soil, rows that are mirrored all the way up her needle-tracked arm.

Corinn claims she is 18 years old, but she appears no older than 15. She says she's been using IV drugs and working as a prostitute for more than a year. She claims she shoots up at least 10 times every three hours and turns tricks to pay the bills. She lives with two other young girls and her 30-year-old boyfriend, who is a drug dealer.

"I collapsed a lot of veins in my arms when I first started, because I didn't know what I was doing," she says, "and when you collapse them, they're gone. So now I have to use my hands."

Two years ago, Corinn lived in Surrey with her parents and her sister. She played in the school band and worked at MacDonald's. Today there is little trace of her former life. "It was my choice," she says, claiming that her parents know where she is but that she doesn't want their help. "I think I just hit a turning point in my life; I just wanted to do my own thing."

Her own thing happens to be one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. About a month and a half ago, she had what is defined in the sex trade as "a bad date." "The guy and me were fighting," she recounts without emotion. "He said he paid me, but I knew he didn't, and he threw me out of the car and ran over my leg. He broke my ankle."

Since that experience, Corinn says, she checks the "bad date list," a monthly publication distributed to sex-trade workers by the Downtown Eastside Youth Activities Society. It gives detailed descriptions of dangerous clients, and Corinn says she believes that the list and her "good judgement of character" will keep her alive.

"Caucasian male. 6 ft. Greyish-shite hair," reads one of the 10 descriptions on the list. "Looks to be in his late 40s. Very handsome man. Driving 2-door red convertible. This guy is going around asking for workers who are 12 years old."

"It used to be an oddity to find a kid on the street down here," says Const. Dave Dixon, an 18-year veteran of policing the perennially poorest postal code in the country. "It would be once every six months or so that you'd find a 12-year-old girl. Now they're going around in groups." Dixon estimates that between 100 and 150 female sex-trade workers aged 12 to 18 regularly work the streets of the Downtown Eastside, and that the numbers are increasing weekly.

"There are so many girls out there, they're giving it away for $20," he says. "So you get these guys driving around, dickering on the price, and they get sex from a kid for $10.

"Meanwhile, kids are dying and younger kids are taking their places. It's really frustrating, because you get to know these kids. I lose probably one a month."

Dixon often goes beyond the call of police duty. He routinely gives his pager number to prostitutes in case of emergency, and consequently, he is often awakened in the middle of the night.

The constable exemplifies a move toward enlightened policing in B.C., a trend spearheaded by the Provincial Prostitution Unit, which was instigated in 1996 to target pimps and johns who sexually exploit youth. The unit is a joint effort by the Ministry of Attorney General, the Ministry for Children and Families, the RCMP and the Vancouver police. One RCMP officer and two Vancouver police officers have spent the past two years educating vice units across the province on how to deal with the issues surrounding child prostitution.

"No person, even at 18 or 19, decides that they want to be a sex-trade worker," says Cpl. John Ward, one of three police officers assigned to the PPU. "They're not born; they're created. Today, the average age of entry into prostitution is 14. By the time she's 20, she's in an arrested state of mental and social development. She can turn tricks but she doesn't know how to open up her own bank account or write a cheque.

"There's a big shift in focus going on with police and social workers' attitudes toward the working girls," Ward says "from looking at street kids as juvenile delinquents to seeing them as they are, victims."

Sandy Jaremchuk works closely with the PPU. As a social worker for the Ministry for Children and Families, she is an active combatant in the war against child prostitution. She has helped set up -- working closely with police across the country -- what she hopes will serve as an early-warning system for kids in trouble.

"The earlier we can locate a child that's headed for the street in Vancouver, the better chance we have of helping them out," Jaremchuk says. When a child is reported missing in Ontario, for example, police or social workers will fax photos across the country. The pictures are widely distributed in Vancouver among volunteer agencies, street workers and police. If found, the child is immediately picked up and taken to a social worker.

"We can stop her and bring her back to interview her, but she doesn't have to stay," Jaremchuk laments. "It can be really frustrating for the police. Some of the kids are brought in 50 or 60 times by the police, and they end up saying 'What's the point?' I'll say, 'Every time you bring her in, it gives me another 15 minutes talk to her.'"

Jaremchuk says that about 30 percent of the kids on Vancouver's street come from the Vancouver area, another 30 percent arrive here from other areas in B.C., and about 30 percent come from other provinces.

Many of them end up turning to the sex trade for money, and those kides congregate in three of Vancouver's main sex-trade areas: the Downtown Eastside -- known as the "low track" or the "drug stroll" because of the predominance of IV drug users in the area and the low prices demanded by the girls -- "boy's town" in Yaletown, and the "kiddy stroll" north of Hastings Street near Victoria Drive.

The so-called high track, located on Seymour and Richards streets near the downtown club scene, is rarely frequented by children, and the prostitutes who work there tend to command the highest fees.

Vancouver's sex trade has a diverse physical and social landscape, but Jaremchuk says there is common ground. "I've never met a kid working in the sex trade who has not been sexually abused. They have absolutely no self-esteem."

Jaremchuk says that just like an animal "smells" fear, a pimp can detect low self-esteem. "When a pimp starts telling them that they're pretty and treats them like they're something special, they begin to think that they owe him something."

In Vancouver, pimps are actively recruiting in some of the most unlikely places. Police and social workers tell nightmarish stories of children lured from high schools, elementary schools, and most recently, from a food fair at the Metrotown mall complex, where pimps have access to hundreds of young girls and boys away from the gaze of their guardians.

"Parents think that when their kids go to the mall with their friends, it's okay," Det. Const. Daryl Hetherington of the PPU says. "But if you go to the mall and see the kids that hang out there, you'd have to be blind not to see that it's not a good place for them."

"The pimps are anywhere the kids hang out," Jaremchuk says. She even remembers one brazen man who tried to recruit a girl right in the waiting room of the Ministry's downtown adolescent street unit, where the girl had gone to see a counsellor.

"I think that a lot of people don't really think that it could happen to an 11- or 12- or 13-year-old kid," Jaremchuk says. "But it does. It seems the smarter we get, the smarter they get. If we close one loophole, they just find other ways of getting around it."

For a pimp, one young girl can be a gold mine: she can earn up to $1,000 a night. Youth sex is sought after on the street because johns tend to believe that the younger the girl, the less likely that she's infected with AIDS or other sexually transmitted diseases.

In Vancouver, the kiddy stroll is one of the main areas where johns buy sex from children on the street. The industrial district comes alive after dark, and there is a constant parade of vehicles: trucks, sedans, two-door compacts and upscale station wagons, each occupied by one man who has come to windowshop for sex. On any given night, there are approximately two dozen girls within a two-block radius. As many as five girls stand on a corner; they are young and from all ethnic backgrounds.

"It would be safe to say that most of the men driving around the kiddy stroll are pedophiles," Cpl. Ward says. "Pedophiles come here looking for children, and we get them here looking from Alberta, Ontario, Victoria and the United States. Vancouver is known as a permissive city."

Indeed, information on buying sex in Vancouver is readily available on the Internet. At one site, the World Sex Guide, you can find an exhaustive list of hundreds of places to buy sex on every continent. Click on Canada and there's a list of 17 cities, not only the major ones such as Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, but smaller ones like Ajax, Barrie, and even Nanaimo. Click on Vancouver and you pull up a dozen pages of testimonials about where to go for what, how much to pay, and how to avoid the police.

One writer, who posted a detailed account of his three-day sex tour, summed it up with: "All in all, Vancouver is great, especially compared to Seattle. You don't have to worry about police busting you or having your name printed if you were busted."

Another wrote: "There are four streets in the downtown area where there're a lot of hot girls... especially the ones who claim that they are over the age of 18... hehehe, yeah right... but there are too many cops there lately," he continues. "Occasionally you'll run into a runaway or something who's really hot."

TUESDAY AROUND MIDNIGHT, and it's like rush hour on the kiddy stroll. The vice squad stops a young blonde girl who claims to be 18 but looks at least three years younger. She has no ID, and police decide to take her to the Ministry for Children and Families' all-night office on Cornwall Street in Kitsilano. She's a runaway from Prince George. She's wearing baggy jeans, brand-new Fila runners, and a Nike windbreaker. Her hair is in a ponytail, and she's wearing very little makeup. She looks like any other kid you'd see at a mall, except her dialogue with police is well-rehearsed. Only her chewed fingernails betray her cool facade.

"I don't usually do this," she says as she climbs into the back of the cruiser. "This is my first time. I've only been standing here for about two minutes. I'm just waiting for my welfare application to go through. I wasn't planning to do this for long."

"If this is your first time, how did you know to come down here?" asks Const. Raymond Payette.

"Everyone in Prince George knows that at Victoria and Pandora there's a track," says the girl, using the street vernacular. "They all know it."

The 10-minute ride gives the two vice officers an opportunity to tell her about the reality of the street: rape, violence and murder. They tell her how 67 prostitutes from Vancouver have been murdered since 1986 and that many of those killings are still unsolved. The is girl is silent for a few seconds, then she begins to bite her nails and sob quietly. "When you're told all your life you're a whore, you start to believe it," she says. "I have a $500 cell-phone bill; someone stole my phone. I have to pay for it!"

A brief conversation with her single mother in Prince George establishes that the girl is, indeed, 18 years old. The woman tells police that a few weeks ago, she flew to Vancouver to convince her daughter to return with her, and she did. A few days later, however, she stole money from her mother to fly back to Vancouver.

"I can't believe she'd resort to that for some telephone bill," says her mother in a later interview. "I'm terribly worried about her, but there's absolutely nothing I can do; she's 18 years old. I've been sending her money to survive to keep her off the street, but that's obviously not working. Until she wants to help herself, there's nothing I can do."

The girl clearly didn't want help that night. She left almost immediately after the police handed her over to the social workers.

"She's a very hot commodity for the pimps because she looks really young," Payette says while walking back to the cruiser. "But if you can get them before their first really bad experience, they're still savable. We picked up a girl from Manitoba who came to Vancouver to make some money to pay some bills. The next time we saw her, she had been sexually assaulted... She's out there all the time now."

IT IS 1 A.M. WEDNESDAY morning and traffic is steady on the kiddy stroll. The Vancouver police vice squad and the Provincial Prostitution Unit are using a police decoy as part of a crackdown on the sexual shopping habits of clients cruising the area.

A young-looking police officer is dropped off on a corner, and several unmarked police cars and vans stand by as a PPU officer runs a video camera to capture the johns on film. The excitement caused by the new girl on the stroll is almost palpable. The other girls are forgotten, and the decoy gets all the attention.

|

"If it was the john's kids wading through condoms, they'd be the first ones at the city-hall meetings."

-- Oscar Ramos

|

The first driver to stop is a young man in a white, old-model Volkswagen Rabbit. The decoy's job is to engage him in a verbal contract for sexual services. He must show her that he has money, and when a deal is struck, she agrees to meet him in a parking lot across the street. A hand through her hair signals that the deal has been made. She meets him in the lot, along with three other plainclothes officers. He is charged with communicating for the purpose of obtaining the sexual services of a prostitute.

About half an hour later, a second car stops to talk to the decoy. His plates are from Washington state; he offers U.S. funds, but there is no deal. He drives away.

During the course of the five-hour operation, four men are charged with communicating. They will appear in court months later, but the Crown will be lucky to get one conviction. As Hetherington put it, they get worse punishment for pulling a U-turn than they get for hiring a prostitute.

"A lot of johns break into tears when we stop them; they beg us to let them go," Payette says. "They're terrified that all this information will ruin their reputations." Payette and his partner, Const. Oscar Ramos, have met hundreds of johns. In fact, for about the past nine months, johns have been the primary focus of their jobs. They designed and operate a new program known as DISC, which stands for Deter and Identify Sex-trade Consumers. The program focuses on breaking anonymity of sex-trade consumers.

"We don't charge them," Ramos says. "We just let them know what they're doing." The officers cruise known prostitution areas and catch johns in the act. "The whole thing came about when we were on patrol," Ramos explains. "People in the neighbourhoods were speaking out because it was happening around the schools and parks. Kids were finding condoms and needles on the streets, so we decided to concentrate on the johns, to force them out of the neighbourhoods, away from the schools and parks. We take down their name, birthdate, vehicle type, description and address. We'll also take note of any details such as a birthmark, tattoo, or baby seat in the back. Most of them don't come back because it's too risky."

"Since January, we've listed 182 names; the youngest is 18 and the oldest is 75. The majority of them are white-collar workers from affluent neighbourhoods," Payette says. According to the data they have collected, 10 percent of them are from the North Shore, 11 percent from Burnaby, 40 percent from Vancouver, and 11 percent from outside the Lower Mainland altogether. "We have yet to pick up one man from the neighbourhood affected."

Ramos adds: "Most of them don't have criminal record, but they're willing to take the risk. And I'll guarantee that if it was their kids wading through condoms on their way to school, they'd be the first ones at city-hall meetings."

DISCOURAGING CLIENTS FROM conducting their business in residential neighbourhoods is one of the Vancouver vice unit's priorities. The "Dear John" program that has been operating for the past few years involves sending a letter to the home of a john that mentions the fact that he has been charged.

By registering names and descriptions and anything unusual, the DISC program goes one step further, and in addition to discouraging clients, it also acts as a database of men who use prostitutes, which could offer police strong leads when a sex-trade worker goes missing or is murdered.

For the past three years, John Lowman, a Simon Fraser University criminology professor, and his colleagues Chris Acheson and Laura Fraser have been conducting a study on the consumers of the street sex trade. Using Internet questionnaires and personal interviews with men charged with prostitution-related offences, they've found that the vast majority of respondents believe it is wrong to buy sexual services from a child. Although estimates of the age at which a person stops being a child varied significantly, only one man interviewed expressed any sexual interest in children.

The study may be affected, however, by the fact that the penalty for buying sex from a child is much stricter than that for using an adult prostitute -- potential survey respondents who have a sexual interest in children may be reluctant to participate in the study, despite its provisions of anonymity. Although Lowman agrees that this may constitute a built-in limitation, his research does reveal that as many as 15 percent of the communication charges he studied involved a child, indicating that there is a quantifiable segment of sex-trade consumers in Vancouver who target children.

The law treats a prostitution offence much more seriously when it involves children. For example, anyone who stops a vehicle, impedes traffic, or communicates with an adult is charged under Section 213 of the Criminal Code, punishable by summary conviction, whith a maximum possible fine of $2,000 and/or six months in jail. When the alleged offence involves a child, that person is charged, under Section 212(4) of the Criminal Code, with an indictable offence with a maximum sentence of five years in jail.

Still, almost no johns ever do jail time. According to the SFU study, out of 434 men charged with communicating for the purpose of prostitution in Vancouver, 87.2 percent were handed either a conditional discharge or an absolute discharge; the other 12.8 percent were fined or received a suspended sentence.

Tough sentences are also unusual under the code's stricter Section 212(4), partly because most johns are first-time offenders -- which usually translates into leniency from the court -- but also because of the language of the law.

Section 212(4) reads, in part: "Every person who, in any place, obtains or attempts to obtain for consideration, the sexual services of a person who is under the age of eighteen years or who that person believes is under the age of eighteen years is guilty of an indictable offense."

The presence of the word believes requires the prosecution to prove that the accused believed that the prostitute was underage, a state-of-mind issue that is almost impossible to document.

Over the past few years, B.C. Attorney General Ujjal Dosanjh has been agressively lobbying for a toughening-up of prostitution legislation in Canada. That effort has resulted in an amendment to federal legislation that allows police to use decoy officers who can structure the verbal contract in such a way that the john makes a deal on the basis of the prostitute's being underage. Once the deal is struck, it is proof enough that the john is breaking the law. This fall, MPs will debate a proposed justice bill that would allow undercover police to wear hidden recorders, a move specifically designed to target clients of child prostitutes.

"It is sufficient evidence to prove that he believed she was young," Dosanjh says. "This has eliminated a whole lot of problems; the courts should not have to decide what the state of mind of the accused is."

Another amendment that Dosanjh hopes will add some teeth to federal law would raise the age of sexual consent between youths and adults from 14 to 16 years. In conjunction with this change, his ministry is pushing to establish a separate offence for adults who seek the sexual services of youths under the age of 14, with a maximum penalty of life imprisonment.

A problem with convicting johns and the pimps who procure children is getting the child to testify in court against the accused. Often the child's life is threatened, sometimes even the lives of family members, and there is the additional stigma of appearing in court and talking in detail about the sexual acts.

To get around this problem, the ministry pushed for the police use of recording devices during the course of the investigation, which could replace the need for the child's testimony.

"The progress has been painfully slow," Dosanjh admits, referring to the pace of legislative change, "I'm hoping that it will not be so slow in the future. I think that we are much closer to the reality on the street than Ottawa is, and I think we are going in the right direction, but it needs to go faster."

Some say the law also needs to cast a wider net. Police and social workers generally agree that the number of sex-trade workers on the street in Vancouver represents only a tiny percentage of the actual number of prostitutes in the trade. Experts estimate that as much as 90 percent of the sex trade is conducted indoors and out of sight, adults and children included, although some would argue that there is probably even a higher percentage of children working indoors because pimps prefer to keep them away from police.

Lowman is outspoken on the problem of on the unseen child prostitutes. "We are not going to do much about the kids in the trade until our politicians start talking about this hypocrisy," he says. "The [Vancouver] municipality is up to its neck in the licensing of prostitution. There has been a proliferation of the sex industry in Vancouver through municipal licensing. So you have this huge percentage of the sex industry going on behind doors, and everyone who can afford to do it off the street is completely immune to charges."

Lowman maintains that the City of Vancouver is actually profitting from prostitution through the issuance of annual business licences. A masseuse who provides a nonsexual, health-based service pays $88 for a one-year licence; a body-rub parlour that provides stimulation "for pleasure," however, pays $6,788 for a one-year licence.

According to one Internet posting on the World Sex Guide: "My experience is that most places which advertise body rubs provide full service in Vancouver. Downtown is more expensive, while Richmond and Kingsway are cheaper."

Another posting reads: "Suffice to say, though, that if you pick up the Courier or the Province and just go to any of the places which advertise in the business personals of the classifieds, you're gonna get some action ...though at some places you'll get more than others, depending on what the girls are willing to do."

Lowman maintains that the reason body-rub salons are not being targeted and the street prostitutes are is "because they are visible and the municipality can't profit from them. They are the scapegoats."

CHERRY KINGSLEY WAS ONCE a child sex-trade worker in Vancouver. That was eight years ago, and today she is one of the most outspoken advocates for sexually exploited children in Canada. She lived in 20 different foster homes after she turned 10, and when she was 14, Kingsley says, she was tricked into the trade by two trusted adult friends who drove her here from Calgary.

"Crystal put makeup on me, dressed me up, and walked me down to Davie Street. She gave me some condoms, told me how much I was supposed to charge, and what I was supposed to do."

It is a classic story lived by countless kids. For Kinglsey, it took years to escape. Most of her friends never did.

"When I look at what happened in my life, I could see some of the things about why I ended up there, and what kept me there," says Kingsley, now in her late 20s. "I know what it's like to be marginalized by society. How people don't let you back in once you've worked on the street -- you're tainted. People would drive by and yell and throw things at us. The fact was that someone could rape, beat and even kill us and there would be no one to complain. A lot of my friends died; dozens of my friends died from drugs, suicide, and murder."

Her experience inspired her to help other children stolen away by the sex trade. In 1996, Kingsley was invited to Stockholm to speak at the United Nations world conference against the sexual exploitation of children. She was one of only three speakers with experience in the sex trade. That conference made her realize there had to be another way to solve the problem faced by millions of children around the world. "As academics and bureaucrats gather together to address these issues, they really don't know what they're talking about," she says. "They need someone who's experienced."

So Kingsley decided to organize her own international conference, with the help of various levels of government and private sources. Her mandate was to focus on the very children who have endured sexual exploitation by listening to their stories and their own solutions. the conference, called Out From the Shadows: International Summit of Sexually Exploited Youth, was held in Victoria this past March, and dozens of government officials from Canada, Europe, the U.S., South America and Central America attended. Kingsley handpicked the "experiential" delegates by visiting prostitution strolls across Canada and Latin America.

Unlike at other international conferences, where the presenting delegates are politicians and people who study the issues, at this summit the governmental heavyweights did not have the floor -- the youths did. All of the more than 60 sex-trade workers told their stories: how they were lured into the sex trade, what kept them there, or how they got out.

"On a personal level, after you tell your story to people so many times, you sort of disconnect from it," Kingsley says, "but through this conference I connected back to my own story, and after listening to the stories of the people at the conference, I started to feel that I wasn't so alone any more."

The summit heard tales of parental abandonment, kidnapping, rape and torture coming from youths living as far away as Halifax and Honduras. But all the stories were remarkably similar.

"I learned that the First Nations youth here in Canada who are working the street are living almost parallel lives with the Central and South American youth," Kingsley says. "They're all living in the Third World, but they're right here in Canada, the children are almost all First Nations. And I think there's a rationalization that goes on in the guy's mind, that 'As long as they don't look like one of my children. then it's okay.'"

Kingsley says that the main outcome to be hoped for from the summit is a will to change things. "I expected, more than anything, a safe gathering to talk about the issues without the shame and stigma, and to develop a vision. I wanted the bureaucrats and politicians and officials to hear the issues and to initiate changes from what they heard."

Changes may be in the offing at an international level. Judith Karp, a member of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, attended the summit and was impressed by the experiential approach. "This conference was a first," Karp says. "They allocated a very short time for the guests like myself to speak, but, in my opinion, this summit can bring out how much youth can become partners to the changes in their country.

"The [UN] committee can give this as an example for other countries to use as a method."

Dosanjh attended the summit as well, and he says it heightened his awareness of child-abuse issues. "Political people like myself, the Crown, police, we sometimes understand these issues in an intellectual way and fail to give it a human dimension in our own mind, and I think what this does for me is bring before my eyes in very real terms the real victims of what's going on in society, and whenever I'm now dealing with this issue, I'll be remembering these young men and women."

Government decision-makers may have been enlightened by the summit, but with hundreds, and potentially a thousand, youths under the age of 18 working in the sex trade in Vancouver, what tangible services are being offered now? Earlier this year, the Ministry for Children and Families announced that it would be funding four more safe houses for children in the sex trade in B.C., which would bring the total number of such facilities in the province to 13 in Vancouver, Kelowna, Prince George, Kamloops, New Westminster and Victoria. The added homes are expected to be open this summer and will mean that there will be 50 beds dedicated to sexually exploited children in B.C.

Meantime, Jaremchuk and other social workers are making do, with a growing demand for help. "Safe houses won't take kids high or drunk, so if detox is full, what do you do with them? It's a lot of trying to find a place to fit the child. The response is not always immediate, and it needs to be."

Const. Dixon is concerned that the number of places for children in trouble doesn't meet the demand. "When you have a kid tell you that she's ready to get into treatment and all you can tell her is the facilities are full and to come back in three months, you know there's a big problem down here."

To deal with the overload, B.C. has been sending children for treatment out of province. In the past 18 months, 10 B.C. kids have been treated at Poundmaker's Adolescent Treatment Centre in Alberta. The facility offers a holistic treatment for children addicted to drugs and involved in the sex trade. The cost per child for the 90-day program is $18,000.

"We have identified that problem, how many we are sending out of province and why," says Michael White, youth-services manager for Ministry for Children and Families. "But we don't have the specific resources locally with a holistic program for these kids."

Meanwhile, White says, the ministry is undergoing a revamping of services with the intention of reallocating funds and using resources more efficienty. White says he hopes some money will be made available to help sexually exploited children more specifically.

Kingsley, though, says that more money and facilities are not necessarily the answer. "We have to change public attitudes, and [then] government will shift as well. At the same time, we also have to shift some of the responsibility out of the laps of government and onto the community. I believe that prostitution could not thrive like it does in a community that doesn't silently accept it. Communities need to protect their children from all forms of abuse. The sex trade has become a community issue through schools, community groups, parents, nonparents, and especially men. I believe men have to address some of their own issues. We have to ask ourselves, why does prostitution thrive?

"The first step toward change is that young people need to tell their stories," Kingsley says. "We have to get rid of some of the myths. We have to get rid of the stereotypes. We have to see that a pimp can be a lawyer who is servicing a client. Pimps can also be hotel managers that charge guest fees, taxi drivers, even the owner of a knickknack store. I have a friend who worked in the back of a tourist shop in Gastown. She was 13 years old and she would sit all day in a little room in the back of the store and guys would come and meet her there. At the end of the day, the owner would give her $20 and a pack of smokes.

"I'm angry, sad and even today I'm haunted by the people I meet who are still on the street. But their strength and honesty and courage inspires me to do something. And I know that with what I'm doing, there may not be any real change in my lifetime," she admits. "But as we empower more and more young people, the change will happen. I'm just trying to plant the seeds for the future."

Meanwhile, for Corinn, as with hundreds of young people who routinely sell their bodies on Vancouver streets, in body-rub salons, through escort agencies and hotels, the changes may not come soon enough. Corinn will continue to live her life in her Downtown Eastside bungalow, planting her bean seeds in the soil and cocaine in her veins.

|

![[Vancouver '98]](van98crm.gif)

![[News by region]](../regioncrm.gif)

![[News by topic]](../topiccrm.gif)